We’ve all seen the famous (or is it infamous?) Venus flytrap do its thing, right? This is one of the coolest carnivorous plants on the planet, and thanks in part to “Little Shop of Horrors,” it’s a pretty well-known one too. In this iconic musical, the plant (known as Audrey II) comes from outer space. However, in the 1960 movie, the star of the show is a cross between a Venus flytrap and a butterwort, both real carnivorous species.

Obviously, Audrey II isn’t the best representation of a true carnivorous plant, either in appearance or “behavior.” So, how much do we really know about these unique plants? Read on…you may be surprised to find out what’s living (and hunting) in your neighborhood.

Please note, this post contains affiliate links. If you click through and make a purchase, I receive a small commission. This doesn’t cost you anything, but it makes me happy…so happy that I might even go out and hug a tree! Thanks for your support! Read my Disclaimer for additional information.

Evolution of the Carnivorous Plant

Venus flytraps are one of a handful of different types of carnivorous plants. Before these species became carnivorous, they were normal, photosynthesizing plants that lived in nutrient-poor habitats, such as peat bogs and other wetlands. They had plenty of water but needed more to survive. This need led to an evolutionary adaptation that produced plants capable of trapping insects, dissolving their bodies, and absorbing the resulting nutrients.

Scientists have studied many aspects of carnivorous plant biology, including the sticky liquid they use to attract and capture prey, and the development of specialized leaves capable of snapping shut, as we see in the Venus flytrap. Interestingly, plants in locations such as North America, Australia, and Asia all use similar digestive enzymes to dissolve their prey, even though these species evolved some distance apart. This suggests there are limited ways for plants to produce digestive enzymes. Some of these enzymes are even similar to those used by non-carnivorous plants as defense mechanisms.

Sundews

Drosera, commonly known as sundews, are one of the largest groups of carnivorous plants. Over 190 species live on every continent except Antarctica. Some species have been known to live up to 50 years. They get their common name from their dew-covered appearance, but that’s not really dew.

These herbaceous plants (meaning they do not produce bark or a similar hard, outer covering) are able to capture small insects by way of the “sticky tentacles” that cover their leaves. These stalked glands secrete a sweet-tasting mucus that attracts and ensnares their prey. Once an unsuspecting insect gets stuck, the glands secrete special enzymes which digest it. As the digestion process continues, a different set of glands absorbs the resulting nutrients for the plant.

All sundews are capable of moving their tentacles in response to struggling prey. The tentacles bend toward the center of the leaf to place the insect in direct contact with the glands producing the digestive enzymes. It doesn’t take much for these tentacles to react. The tiniest insect can set them off.

Drosera is a relatively old genus, evolutionarily speaking. A more recent branch on the carnivorous plants’ ancestral tree is the Venus flytrap.

In 1875, Charles Darwin wrote that the Venus flytrap is "one of the most wonderful [plants] in the world."

- Charles Darwin, "Insectivorous Plants"

Feed Me, Seymour!

Although I wanted to focus on some of the more lesser-known carnivorous plants, I certainly couldn’t write an article about “flesh-eating” plants without describing the Venus flytrap in more detail, now could I? However, I chose to start with Drosera because it’s an earlier ancestor of the Venus flytrap. I know; they look nothing alike. Stick with me (see what I did there?)…

Obviously, the Venus flytrap looks like a carnivorous plant. It has those specialized leaves that are just waiting to chomp down on an unsuspecting beetle or spider. That’s certainly cool, but how does the plant do it? After all, it’s not an animal. It doesn’t have muscles to trigger the trap.

This is where things get really amazing. The Venus flytrap is native to subtropical wetlands on the eastern coast of the U.S. (mainly North and South Carolina). It catches its prey by way of a “trap,” located at the end of each leaf. Inside the trap, tiny “trigger hairs” wait for an insect to brush against them. However, in order to avoid closing the trap unnecessarily, the plant doesn’t react after only one touch.

If the insect makes contact with a second trigger hair within 20 seconds of the first touch, the trap will be sprung. This helps the plant avoid shutting and reopening the trap (which uses a considerable amount of energy) when a false trigger such as a raindrop or the wind moves the hairs. Once inside the trap, the struggling insect must touch five more hairs in order for the digestion process to begin, another safeguard against wasting energy.

The edges of each side of the trap are lined with stiff cilia that link together to prevent larger prey from escaping. Prey that is very tiny, on the other hand, can slip through the cilia. This is likely because digesting such small insects would not be beneficial for the plant, especially considering the amount of energy required for the digestion process. If the prey escapes, the trap will typically reopen within 12 hours (assuming it has not outlived its lifespan).

Venus flytraps commonly consume beetles, spiders and other crawling arthropods. They don’t catch flying insects very often. The average diet of a Venus flytrap consists of 33% ants, 30% spiders, 10% beetles, 10% grasshoppers, and less than 5% flying insects.

On the other hand, Drosera (the Venus flytrap’s early ancestor) predominantly consumes small, flying insects. The Venus flytrap’s more “modern” design allows the plant to capture and digest larger insects that would easily escape the sticky tendrils of the Drosera plant. Many scientists believe this gives the Venus flytrap an evolutionary advantage over the sticky trap design that is common in other carnivorous species.

Although carnivorous plants have been around for a long time, there is no fossil evidence of the steps involved in their evolution from ordinary wetland plants to the tiny “killing machines” they are today. This is primarily due to their lack of bark or wood, which would make fossilization more likely. Despite this lack of clear evidence, researchers have been able to piece together a proposed method of evolution that explains how the Venus flytrap developed its “leafy jaws.”

Photo Credit: CarnivorousPlantCare.com

Butterwort

Butterwort isn’t really a name that strikes fear into those that hear it, but it should…if you’re an insect.

The butterwort is another one of the coolest carnivorous plants on our planet (genus Pinguicula). Butterworts use a “sticky trap” to capture prey. They are common to Europe, North America and parts of northern Asia. Roughly 80 species are currently known worldwide.

Instead of using sticky tentacles to attract potential prey, butterworts simply produce an enzyme that looks like droplets of water sprinkled across the surface of their leaves. This attracts insects in search of water. When an insect comes into contact with these drops of mucus, it becomes trapped, and the plant releases more of the sticky substance, along with some digestive fluids, to further prevent the insect’s escape.

A second type of gland on the leaves releases additional, more powerful digestive enzymes which break down the parts of the insect’s body that are digestible, leaving behind the exoskeleton. The resulting nutrients are then absorbed by the leaf through tiny holes, similar to how the drain in a bathtub works. The exoskeleton eventually blows away or falls off the plant.

There are two basic groups of butterworts based on the climate in which they live: tropical and temperate. Tropical butterworts are carnivorous year-round, but temperate species have a dormant period during the winter months when they do not produce digestive enzymes. Both groups flower, producing brilliant blue, yellow, or violet-colored blooms. The flowers sit atop long stalks to ensure pollinators don’t become trapped on the leaves. Butterworts are often cultivated and hybridized because of these hardy flowers.

Pitcher Plants

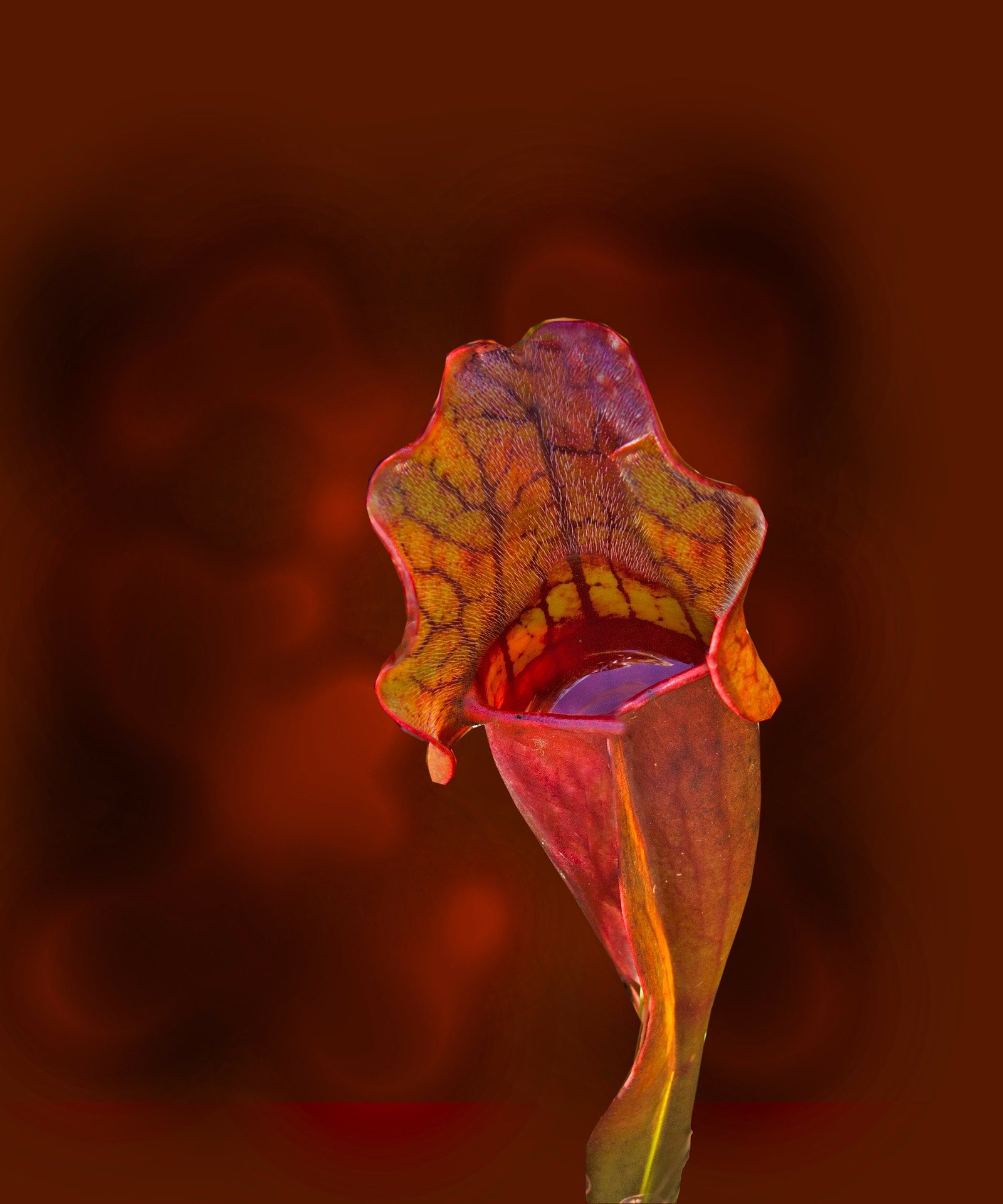

This final carnivorous plant doesn’t look very carnivorous at all: the pitcher plant. These unique plants are quite beautiful, with a modified leaf that’s similar to the Jack-in-the-Pulpit, calla lily, or trumpet creeper. However, beauty can be deceiving.

There are two families of pitcher plants: Nepenthes and Sarrancenia. The Nepenthes, which are primarily tropical, are considered “Old World” pitcher plants. They are characterized by their smaller (located on the tip of the leaf) pitchers, waxy coating on the inside of the pitcher, and preference for climbing up into the canopy.

New World pitcher plants, the Sarrancenia, are ground dwellers, and the pitcher is derived from the entire leaf, rather than just the tip. Plants in this genus are frequently mistaken for normal, non-carnivorous species, as they look similar to other flowering plants. They are found in North and South America.

Pitcher plants produce “pitfall traps,” a deep cavity filled with digestive fluid. Flying or crawling insects are attracted to the plant by nectar or a visual bribe (such as a bright color). The rim of the pitcher is typically slippery, which causes the insects to slide down into the trap. Some species of pitcher plants have waxy scales, folds, or downward pointed hairs located on the inside of the pitcher to prevent insects from climbing out.

Once an insect falls into the pitcher plant’s trap, its frantic attempts to escape trigger the plant to produce strong digestive enzymes. The insect eventually drowns in the fluid and is consumed. Some pitcher plants house certain types of insect larvae that feed on trapped prey and then excrete nutrients the plant can absorb.

Growing Carnivorous Plants

If you’re thinking about raising your own little, green “killing machine,” you’ll want to do some additional research. Begin by finding a reputable garden center to buy your carnivorous plant (or try Amazon). Some species are advertised as “easy to grow.” This can be the case if you take a few things into consideration first:

Don’t play with flytraps, leaves or tentacles. Prodding them will make them fall off. Individual flytraps in particular have a limited life span and can only close and reopen four or five times before they die.

Plant in soil that is designed specifically for carnivorous plants (see my recommendations below for examples).

Don’t water with regular tap water. These plants usually live in nutrient-poor soil. The minerals in your tap water might be too much for the plant.

Feed your plant little bugs once or twice a month. If the plant is outdoors, this won’t be necessary. Carnivorous plants can survive without these additional nutrients, but they’ll do much better with them.

While carnivorous plants may be the bullies of the plant world, they’re also incredibly interesting, both from an evolutionary and entertainment perspective. As humans, we’re fascinated and a bit freaked out by these strange and mysterious plants. I hope this article enlightened you. Perhaps, like me, you have a sudden desire to add a new “pet” to your tribe. If you already have a carnivorous plant in your home, let me know how it’s doing!

One last thing: although I am always a fan of tree (or just plant in general) hugging, I don’t recommend it with these little guys!

Related Articles

If you enjoyed this article, you may wish to read these as well!

Craft a Clay Leaf Bowl

Have you ever noticed how many different varieties of leaves exist out there in the wilds of your neighborhood? Don’t worry if your answer to that question is “no, not really.” Most people don’t pay much attention to leaves…until they have to rake them up, that is! Well, with this simple, clay leaf bowl project, you’ll definitely start noticing the beauty of leaves...

DIY Garden Label Stakes

So, as much as I would love to brag that I’m a natural green thumb, that would be a little white lie. To put it simply, I have a tendency to kill green things. It’s sad, but true. Don’t get me wrong, I love planting flowers, herbs, and vegetables. They just don’t love staying alive every time I do. Honestly, I think I enjoy crafting DIY garden label stakes and other outdoor decorations more than tending the actual garden...

Life on the Forest Floor

You’ve probably already learned about the forest layers in science class, but I bet you didn’t pay much attention to the floor of the forest during your studies. All the cool plants and animals are up in the canopy, right? Not necessarily…